Susan Raffo

Now blogging at. https://www.susanraffo.com/

Wednesday, April 10, 2019

Wednesday, March 13, 2019

Generational trauma and knowing who your real enemy is, it's all about the blood

I wrote this only days before the horrific attack in Christchurch, New Zealand, in which 49 people, children, adults, elders, were murdered in a terrorist attack, after the ongoing attack of Ilhan Omar because of words she named about the state of Israel. What I am writing about here is real. It is real in the way of leading to violence in its most physical form. I hold my prayers for those killed in Christchurch and for those murdered, generation after generation, because of what is written here. This is not just a history lesson.

-----

There is a line that keeps running through my head. It’s from the Hunger Games, when Finnick tells Katniss, who feels the chaos of not knowing who to trust, of not knowing who started what kind of violence and how she can feel safe, “Katniss”, Finnick says, “remember who the real enemy is.”

I was angry - and confused - for a lot of years about who my real enemy was. What happens when the people who love you, who are there to take care of you and protect you from when you are very small, don’t do that? What do you do with the chaos when the kin who are supposed to be in it with you actually cause even more harm? I picked leaving home, moving far away from my people, calling them out from a distance while creating new stories about why things turned out the way they did. I chose a whole bunch of space and time to figure out how to make sense of the chaos so that I could come home again. And after a time, the real enemy started to become clear. There is a lot of chaos and call-out happening over Representative Ilhan Omar’s critique of the state of Israel. The responses to Representative Omar, and the responses to the responses, carry deep pain and anger. Reactions and then the reactions to the reactions are emotional, some are overly rational and many are dangerous, using the weapons of Islamophobia, anti-Black racism, indigenous disappearance and anti-Semitism with some misogyny and sexism thrown in to build a case. This level of reactivity, of intense response, means that this moment is not about the present moment. It is not about an act of physical violence, of flesh harming flesh. These reactions are to words. The intensity of these reactions are a demonstration of the impact of generational trauma.

Somewhere, there is an original wound. When violence and other forms of held trauma do not have the space to heal and integrate, then they are passed forward. Somewhere is the shape of violent disregard so intense that, generation after generation, it has moved forward as culture, as protection, as surveillance, as pain. Within the cycle of violence, all players evolve protections in order to survive. We develop protections around how we have been harmed and how we have caused harm. And then over time those protections become culture or community practice and their origins become invisible.

Chaos theory says that if we stand back far enough, there is always a pattern to emerge. Chaos is rarely chaos; we’re just in the middle of too much information without a sense of how it’s all connected to each other. Chaos is how systems of supremacy unsettle resistance. When you combine chaos with the triggering of deep fears about your ability to be ok, to survive, to be safe, then it becomes almost impossible to step away from the pattern and see clearly. Healing from deeply held trauma needs space and enough safety for the body to move through something vulnerable. State violence and surveillance and internalized violence and surveillance prevent this space and safety from emerging.

Anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, indigenous disappearance and anti-Black racism would not exist if it weren’t for the violence that, over generations, emerged as the twinning of Christian supremacy and capitalism. White supremacy wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for the twinning of Christian supremacy and capitalism, two belief systems that evolved at the same time.

I was angry - and confused - for a lot of years about who my real enemy was. What happens when the people who love you, who are there to take care of you and protect you from when you are very small, don’t do that? What do you do with the chaos when the kin who are supposed to be in it with you actually cause even more harm? I picked leaving home, moving far away from my people, calling them out from a distance while creating new stories about why things turned out the way they did. I chose a whole bunch of space and time to figure out how to make sense of the chaos so that I could come home again. And after a time, the real enemy started to become clear. There is a lot of chaos and call-out happening over Representative Ilhan Omar’s critique of the state of Israel. The responses to Representative Omar, and the responses to the responses, carry deep pain and anger. Reactions and then the reactions to the reactions are emotional, some are overly rational and many are dangerous, using the weapons of Islamophobia, anti-Black racism, indigenous disappearance and anti-Semitism with some misogyny and sexism thrown in to build a case. This level of reactivity, of intense response, means that this moment is not about the present moment. It is not about an act of physical violence, of flesh harming flesh. These reactions are to words. The intensity of these reactions are a demonstration of the impact of generational trauma.

Somewhere, there is an original wound. When violence and other forms of held trauma do not have the space to heal and integrate, then they are passed forward. Somewhere is the shape of violent disregard so intense that, generation after generation, it has moved forward as culture, as protection, as surveillance, as pain. Within the cycle of violence, all players evolve protections in order to survive. We develop protections around how we have been harmed and how we have caused harm. And then over time those protections become culture or community practice and their origins become invisible.

Chaos theory says that if we stand back far enough, there is always a pattern to emerge. Chaos is rarely chaos; we’re just in the middle of too much information without a sense of how it’s all connected to each other. Chaos is how systems of supremacy unsettle resistance. When you combine chaos with the triggering of deep fears about your ability to be ok, to survive, to be safe, then it becomes almost impossible to step away from the pattern and see clearly. Healing from deeply held trauma needs space and enough safety for the body to move through something vulnerable. State violence and surveillance and internalized violence and surveillance prevent this space and safety from emerging.

Anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, indigenous disappearance and anti-Black racism would not exist if it weren’t for the violence that, over generations, emerged as the twinning of Christian supremacy and capitalism. White supremacy wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for the twinning of Christian supremacy and capitalism, two belief systems that evolved at the same time.

In the 4th century, Emperor Constantine* converted to Christianity, turning the machinations of the Roman empire into a tool for two things: grabbing land and other wealth AND converting everyone in its path to Christianity. As part of this, in 318 Constantine brought a whole bunch of Christian bishops to a meeting to create the rules of Christianity (called the Nicene Creed). Before this, Christianity was a mixed bag of belief systems including both highly patriarchal structures and highly matriarchal structures, including communities that resembled Buddhist monasteries, communities that believed in sexual pleasure as an expression of God’s divine love, communities that were still predominantly Jewish with a few changes in tradition, and more. The Nicene Creed named Christianity as the single true belief system. Over a period of generations, the pre-Christian beliefs of Rome were wiped out, sometimes violently and sometimes by conversion.

Anti-Semitism grew in shape and practice along with the growth of the Christian church, its violence waxing and waning, shifting shape and practice, but never disappearing for all of Christianity’s 2000 plus years**.

Originating in European Christianity, antisemitism is the form of ideological oppression that targets Jews. In Europe and the United States, it has functioned to protect the prevailing economic system and the almost exclusively Christian ruling class by diverting blame for hardship onto Jews. Like all oppressions, it has deep historical roots and uses exploitation, marginalization, discrimination and violence as its tools. Like all oppressions, the ideology contains elements of dehumanization and degradation via lies and stereotypes about Jews, as well as a mythology. The myth changes and adapts to different times and places, but fundamentally it says that Jews are to blame for society’s problems. From Understanding Anti-Semitism.

The political growth of the Catholic church has depended on the tools of anti-Semitism to grow its own wealth. The history of anti-Semitism is the history of Christianity evolving an idea of “pure blood” and dangerous blood, of good and bad as essential qualities of a person rather than a type of behavior. These ideologies of dangerous and pure blood could then justify actions that otherwise go deeply against Christian values of life and forgiveness, of community and radical love; go against those values while seeming to stay in alignment with the same values. This ideology evolved along with the Christian idea that being closer to God means transcending or leaving the body. The body becomes a site of control and good bodies go to heaven while bad bodies are dangerous and must be controlled. Histories of blood sacrifice and transcendence as a part of spiritual life are almost universal, with traditions found on every continent. The development of the political Christian church used these practices as a tool for justifying the accumulation of resources through the destruction of other people, cultures and communities. This is not the only time that this has happened. This is what happened that led to our present moment.

In the middle ages, the Roman Catholic Church employed soldiers through the Crusades or what was called the Holy wars. The Crusades especially targeted those lands of the Eastern Mediterranean, where Islam was a growing spiritual and political force. For reasons of religious conversion, in order to bring alliance among different Christian factions, and for wealth accumulation, the Crusades strengthened the idea of the Pope as the head of the Catholic church and normalized militarism as a part of religious practice. Jewish communities, “heretical” Christian communities, pagan communities and Islamic communities were attacked or often destroyed. The boundaries of the political-religious western Christian world were defined as a result of the Crusades and the political wealth of the Christian church was strengthened. Orientalism, as named by Edward Said, was the justification narrative that allowed this stage of western colonization to expand while, again, maintaining Christian Europe’s sense of living in alignment with its own values.

The sense of Islam as a threatening Other - with Muslims depicted as fanatical, violent, lustful, irrational - develops during the colonial period in what I called Orientalism. The study of the Other has a lot to do with the control and dominance of Europe and the West generally in the Islamic world. And it has persisted because it's based very, very deeply in religious roots, where Islam is seen as a kind of competitor of Christianity. Edward Said in Orientalism.

Christian supremacy continued to grow, changing shape and practice depending on the country and historical moment. When the British government began to colonize the lands of the Americas, joining other European countries in the use of the institution of slavery and indigenous destruction as the primary policies of wealth accumulation, it grafted the idea of pure and dangerous blood on to the bodies of those it was targeting. This same strategy of justifying some bodies as bad and some bodies as good enabled the British and then later US governments to continue to build wealth off the bodies and lands of indigenous and Black people while still believing it lived its Christian values. The invention of the one drop rule meant that one drop of "Black blood" made you Black and therefore controllable by white supremacy whereas Blood quantum meant that you had to have a specific amount of "indigenous blood" in order to count as Native and therefore be recognized by signed treaties. Blood rules helped define strategies of surveillance used in times of war to contain the bodies of those who resisted: reservations, prisons, and then, over time, the cultural practices of educational systems, healthcare systems, and all other methods for disseminating culture. At the same time, religious practice became increasingly focused on transcendent practices, a sense of leaving the body to find relationship with God, of becoming pure Spirit, a sanctified dissociation that also supported those causing harm to not feel, in that most physical of senses, the impact of their actions.

In the early 20th century, independence movements in lands colonized by western Europe began to surge forward and an increasing western need for oil merged together. The same essentializing idea of pure and dangerous were now directed towards Islam, justifying Western war mentality by calling the Islamic world and Arab countries barbarous, cultures in need of ‘civilizing.’ The Western cultural practice of orientalism created fertile ground for the violence of Islamophobia. This became heightened as a result of 9-11 and once again, trauma repeated itself. Christian fear swelled and the need to offset that terror on a clear enemy turned into the rapidly evolving practices of Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism.

Anti-Semitism, anti-Black racism, indigenous disappearance, and Islamophobia are all manifestations of the same early trauma and override: the desire for wealth accumulation, the violent taking of lands and resources and bodies to accumulate that wealth, and a need to feel in alignment with deeply held Christian values. They all depend on this idea that some blood/people are dangerous and not quite human while others are pure and that it is possible to do great violence and still be a good Christian. Andrea Smith powerfully names this history in her piece, Heteropatriarchy and the Three Pillars of White Supremacy.

Christianity also evolved in European owning class communities to support a dissociation from the physical body and an essentializing of bodies that are “different” as needing to be controlled or dismissed. When Constantine paid for the construction of a singular unforgiving Christian doctrine that was then used to justify the expansion of Empire, he took a grassroots belief system that centered the ending of poverty and radical love and turned it into a tool of violence. Western Europe used that legacy for the development and then expansion of market capitalism. You could not have capitalism without Christianity and you could not have the spread of Christianity without capitalism.

Systems of belief have protective survival responses. They are held in the nervous systems of all of those who have been raised within those systems of belief, both the perpetrators and those who are harmed. In moments like this, I see multigenerational systems as having a kind of energetic form, their hands holding the marionette strings and making us dance. We lost a lot in the scientific world when we stopped talking about evil spirits. Sometimes I think it’s the only way to make visual the way these multigenerational patterns live through us, forcing so many of us to be agents of their harm even as we seek to destroy them.

What is happening right now is painful. And it carries with it a whole range of individual and collective experiences that have taken place since the expansion of the Roman empire and probably before. Without transformation, the cycle of violence always moves forward and those who have been harmed, too often, become those who carry the harm forward. Shifting the complex paths of pain that are twisting so tightly in the conversations and reactions swirling around Representative Omar’s comments is about more than remembering history. But remembering history is deeply important. This mess started somewhere.

All of my family lines are Catholic with the majority of them being Catholic as far back as can be remembered and with some of us Catholic through forced conversion within recent generations. Some of my ancestral lines represent the people who were also first colonized by the Roman Empire and who then became the ones to benefit from and move forward that wheel of violence. I assume and sometimes know that somewhere in my histories are people who supported or benefitted from anti-Semitism, the Crusades, the stealing of land, and the enslavement of free bodies. As is true with all empires, most of my people were living their lives, using their Church as the place to support their grief and family transitions. They were not thinking about strategies for wealth accumulation and that wealth rarely trickled down to their families and kin. And as is true with all empires, each and every one of us is still, in some responsible for the repair. It’s about time that energy and pain that is wound around and between those hurt by and raging against Representative Omar turn around and direct that energy towards us. Sometimes you have to look far enough back across the space of history to begin to see a pattern in the tangled mess of the present moment. Sometimes you have to look far enough back to understand why those who seem to be causing you harm are, themselves, stuck with you in a pattern of pain. In my own family, this meant looking for enough back to find the common thread that causes some of us to turn to our own kin and hoist our hurt on each other’s bodies rather than come together to fight against the violence that has become woven through our lineage.

In the midst of chaos and generations of pain, it’s important to know who your real enemy is, your original enemy, the one who continues to benefit, especially when those who were first hurt are overwhelmed with chaos and striking against each other rather than turning to the ones who first set the violence in motion.

* Violence begets violence. So why start with Constantine when there must have been a before? Did Constantine’s class/mixed upbringing, his witness of the Great Persecution in which state policy was to destroy all Christians, a literal genocide, before Constantine came to power and shifted state policy to use Christianity as a means to an end? And then what was the before for that?

** The political Church is not always the same as what regular folks do on the day to day. While there have always been people who have used the political Church to further their own ends and to cause harm to others, many people truly seek to be faithful and to follow the values they believe in.

Monday, March 11, 2019

pushing pulling and making change

Sometimes I am going to share practices or activities for helping you and your kin, the folks you work with, bring different kinds of embodiment or movement play into your work. This is an open sourced workshop. Go ahead and use it. Ask me about it. Bring me to do it with you. If you use this, please just credit where you learned it from. I learned what is on this page from Suzanne River, now passed, who learned these elements from Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen through the School for Body Mind Centering. Gratitude to Alejandra Tobar Alatriz for playing with me and helping to create and earlier and first version of this workshop.

Pushing, pulling and making change: a 90 minute workshop

This workshop is used to explore the developmental patterns of the body that are integrated through life, supporting our bodies abilities to move, make change, integrate information and make connections with other people. Here, the workshop is used as a kind of lab or practice space to look at the collective body eg: our organizations, our collaboratives, our collectives. Through movement and information, individuals are invited to look at their social justice work critically, identifying “stuck” places or opportunities for different kinds of action. Every directive in here can be modified to meet your body's abilities and needs.

Framing time: 5 minutes

- Frame: this is a form of practice and learning, this is a kind of lab. This isn’t about getting anything write but it’s about surfacing information, noticing what comes up but not attaching to it. Just noticing.

- All life moves as a pattern of contraction and expansion. Every cell. Every organ. Every living organism. Every family. Every community. The planet. Expansion and contraction is what makes movement possible. If you break expansion and contraction down, you get a series of steps: yield, push, reach, grasp, pull, with a pause or moment of intention between each one. These are also the basic developmental movement patterns of infants: the steps we repeat as we learn how to move from a life lived only in fluid to the ability to jump in the air and catch a ball. These are also the steps we go through in order to build trust with our environment.

- Today’s practice is to play with these movements: with the movement of yield, of push, of reach, of grasp and of pull. To sense where there is ease and where we are awkward. To notice where we can play or fluidly move and where we can't. This practice lifts up information. All through our work for liberation, we are going through the same steps: needing to sometimes yield, to sometimes push, to sometimes reach or grasp or pull. Everyone of us has habits; some things we do more often and other things we avoid. Don’t assume you know which is which for you or for someone else. Play with these movements and see what happens.

- Take care of yourself with the movement, go where you feel comfortable, make any necessary accommodations. Remember, stillness is also a form of movement. So is breathing.

Movement: 30 minutes

- Move into the developmental stages - movement practice without theory - yield - push-reach-yield-grasp-pull

- Start with tonic lab. This is also shivasana in yoga. It’s the first reflex the body has; lying on the floor and feeling gravity. Start here. Let yourself fall into gravity.

- Move to standing as you are able. Notice how this movement happens. Be curious.

- In your own space, invite your body to feel what it is to yield. To push. To reach. To grasp. To pull. Feel them clearly. Merge them. Play with them. Listen to yourself.

- Partner with another person. Do the same using each other’s hands, bodies as the other against which you pull or push. Notice what feels easy. Notice what feels awkward. Listen to what comes up in you as you practice your own development against and with the body of another.

Framing/information language: 5 minutes

- Some language about the developmental patterns and the body

- There is a pattern for how our individual bodies engage with other individual bodies as part of a broader collective body through relationship (baby against mother, developmental stages that move us towards separation, patterns that are then repeated in all of our friend/lover/colleague relationships). These have been created through an evolutionary process. They are always playing out when we are together. They are impacted by power, by intimacy, by our individual and shared physical sense.

Group exploration exercise: 15 minutes

- Put sheets of paper up on the wall

- Frame: now this is the lab moment. What we believe is that any kind of change we make, any kind of activism, comes from the collective body seeking fuller embodiment/presence. What we are inviting this group to do is now be in learning lab together and to see what happens when we apply all of this to how we make change. Remember, for the purpose of this workshop, we are thinking of activism as collective strategies for making collective change. Think of different kinds of change work you are involved in - either now or in the past. Another point, everything can be a tool or a weapon.

- Break into small groups of three and reflect on the following questions

- What is great or useful about each of these patterns? How does it have the potential to move your work forward?

- What can potentially hinder collective process?

- All groups share out on the pages on the wall

Movement practice: 10 minutes

- Movement break: We are going to use movement to experience the patterns again but now we will do them as a group. Because we still don’t know each other, there are a few boundaries. For one, we don’t assume that we’re about to get in a great big puppy pile of bodies. You can choose if you want to touch or be touched by others. But move into your group. Start exploring and playing with the patterns but the point of this is to notice how the other people in your group affect you. As you move, notice if their reach shifts your push. If you feel compelled to move away from someone when they are reaching, if you feel the desire to lean into their push. Notice how your individual self is impacted by the others around you.

Transition: 5 minutes paired check in.

- Transition - five minute check in with your group. What did you notice?

Group conversation: 15 minutes

- For each of you, notice: what patterns feel more habitual, accessible or cultural? What patterns do you privilege in your movements? Your work? Your relationships? Which feel the least embodied or available as a tool to support your life? Your work?

- Full embodiment of our change work means having available to us all of these movement patterns at all times. It means being able to shift between them within five minutes or within five hours or within the space of a week. Any pattern held or maintained over a long time is not sustainable. Pushing and pushing and pushing is both exhausting and limiting.

- If there is time, more conversation about this.

Ending circle: 5 minutes

- In expanding, I

- In contracting, I

Tuesday, January 02, 2018

Resourcing cells, fundraising communities, and economic justice

Every single cell in your body has only three seconds of oxygen available at any given point. Just three seconds. Without oxygen, your cells will die. And yet every cell in your body just keeps on expanding and contracting, knowing in some deep instinctual way, that fresh oxygen will come as needed. And the great majority of the time it does. And so you stay alive.

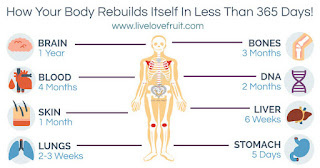

Within each year, the body rebuilds itself multiple times over. Our life is constantly moving, constantly growing and changing and integrating the new into something different. This would not be possible without that underbelly of cellular trust. Three seconds of oxygen and then comes the rest of our lives. Breathing.

Back in the late 90s early 00s, with a group of people I started a newspaper called Siren. Our tagline was inciting conversation and our vision was to have a city newspaper that read like a conversation between everyone who lives here. This means our writers had to write every article so that it could speak to someone who knew nothing about the article's subject and to a person whose life story had just been reported. Restaurant reviews were written as though the reader was hearing someone talk about their home food and for the reader with no idea this kind of food even existed. The same for news stories and art reviews and music reviews. We didn't always get it right but we kept trying.

When Siren started, I knew nothing about business. I didn't want to know about business. I didn't want to know about budget sheets and advertising and spending plans. So I stepped away from that part of the work, keeping my focus on the editorial and the vision for the paper. I assumed they were different things, not connected at all. I had a lot of justifications for this because really, the rational mind can justify anything, but underneath it all, the business and money side scared the shit out of me. I thought it wasn't political enough or interesting. And so I stepped back.

The newspaper folded in two years for all kinds of reasons but the biggest one was that we didn't have enough cash for a project this big. The second biggest reason is that we hadn't done enough trust at the front end to deal when our values crashed around content versus cash. We fought. A lot. And it was painful, for all of us. While at the time I was full of self-righteousness about the paper's ending, the gift of distance means that I now know, tail between my legs, how I contributed to the crash.

A year or so after Siren closed, I started learning about fundraising. I was tired of being afraid of money and letting that fear actually hurt me and the communities I loved. I didn't want to be rich or earn a shit ton of cash. I wanted to make sure that no fierce and loving vision for change and connection withered and died because deep economic injustice is real in the US of A.

Like healing and organizing, resourcing the body and fundraising from communities are the same thing. The fact of their seeming difference comes from believing that the individual is separate from the community and from all of the life that is around us. Every cell lives with only three seconds of oxygen and the absolute ability to know that more oxygen is coming. The body does not separate from the things it needs: nourishment, water, oxygen. Not every part of the body is impacted by these things in the same way and yet all need them to survive. The root, stem and leaf of a planet have different relationships to the water, nourishment from the soil and carbon from the atmosphere and yet, all need them to survive.

I was mostly paying my bills from fundraising work when I began to study craniosacral therapy. Almost immediately I saw the links between these different kinds of resourcing. It all makes sense, doesn't it? There are enough resources to support our collective basic needs. There are restrictions in those resources that are set up by unfinished histories, by the policy of extraction for profit (a form of capitalism) that defined the US as a corporate state from the beginning, one aspect of its original wound. Fundraising, when it is in right relationship, works to release or move around some of those restrictions. The same is true for the physical body; histories have set up restrictions in the tissues and bodywork supports releasing or shifting our relationship to those restrictions so that we have access to more of our life force. For awhile I met in regular conversation with two beloved friends, David Nicholson and Kate Eubank, to play with the relationship between those two things. We came up with a workshop or approach to thinking about resourcing community work that tried to learn from the body rather than from the systems around us.

As healers and healing practitioners, our work is about supporting each person we work with to feel and experience and deepen and grow their own resources. We work with their muscles to better experience their binding and lengthening factors. We work with their skeletal structure supporting its alignment so that the bones can have a more fluid and solid stacked relationship to gravity. We work with the fluid body, supporting the place where we live as whole integrated selves connected to all life. And we support nervous systems and circulatory systems and energetic systems to remember themselves and feel the nourishment of care. As healers and healing practitioners, most of us have some deep level of trust that part of changing the world is about supporting people to more fully feel and experience their own lives.

This is good. This is powerful. This is not enough. All energy needs to move. All life needs to move. All healers have to move dollars and other resources in support of the collective body. And all people involved in moving money have to learn about healing, both the individual and the collective selves. Period.

One of my favorite sayings these days is that we are all in the middle of the wound while we are trying to heal the wound. This means that how we have been hurt and survived defines how we even think about transformation. The way we have loved and connected despite the shit also feeds how we know that liberation is possible. Both are true. And for me as a bodyworker, my responsibility is to shift the conditions around healing and bodywork as much as it is about showing up in right relationship in the bodywork room.

Two or three times a year I am going to use this blog to try and move some cash from places where there is extra to places where more is needed. And I am going to ask you to do the same. I'll ask you to do it with me or to do it on your own. And I'll share what I've learned and ask you about what you've learned. And maybe out of this, we'll support some of what is tight to get a bit more fluid.

Here is what I am doing right now to weave together the resourcing of the individual body with the resourcing of community, to bridge the false gap between healing and organizing, and to then please god just get out of the way and let liberation take its own path. I don't assume this is enough or even the right answer, it's just the right answer that I hear whispered in my dreams when I ask ancestors and spirits, what next?

First, supporting a cohort of Native, Black, Brown, trans and queer biodynamic craniosacral therapists. This feels huge to me. It feels urgent. I am not going to list all of the horrible things that are happening and have recently happened that underscore the need for both ending violence and then supporting the healing of those impacted by violence. There are so many who right this second need to tolerate the intolerable. Click the link and read more about this dream and vision. And by dream, I mean literal dream. Like ancestors showing up amidst the snores, crossing their legs, raising an eyebrow and saying, hey descendant, get your ass moving.

A bit more context for this fundraiser: when the American Medical Association was created in the 19th century, its focus was on determining which kinds of healthcare were real and which were quackery*. At the time, outside of cultural healing traditions within tribal lands and elsewhere, homeopathy was the highest used form of healthcare within what is called the US. Allopathic or what we call western medicine had a smaller community of support. After the AMA was formed, multiple types of healing were discredited within the mainstream (meaning primarily European descended and government supported) world. Practices like midwifery, working with plant medicine, healing touch, acupuncture, bone setting and more were practiced in Black communities, in Native and other indigenous communities, and in immigrant and refugee communities. One of the strategies for building and shifting white supremacy was to build identity around those who followed "scientifically proven" medical methods and those who practiced "primitive" forms of care. Over time, those "primitive" forms of care (which, of course, still worked) were then made illegal, particularly in the cases of tribal cultural practices of care, midwifery and acupuncture. Healing traditions evolve over generations, tied to a community's language and cultural ways of passing on meaning and survival. Forcing away a community's healing traditions is another aspect of the violence of supremacist culture. This fundraiser and cohort is only one very small not enough moment in attempting to respond, as a healer, to the truth of this violence.

Second, supporting the People's Fund at the People's Movement Center. This fund supports free and reduced bodywork and sustainable supported bodyworkers. A basic win win.

If you can give to both, give to both. If you have to pick one, please give to the cohort. Right now. Supporting something like 15 Native, Black, Brown, queer and trans people to build their own practices is about supporting circles to keep expanding outward. This is not enough. There needs to be more. This is still something.

Our bodies know how to live as though there was enough. We rebuild ourselves, cell by cell, every day. Only three seconds of oxygen and yet, each cell keeps contracting and expanding. Our bodies remember what it is to know that there is enough. Shifting how the collective body holds the resources of money and time and knowledge and practice so that individual bodies can, together, begin to experience what our cells already know is one part of our larger work of liberation.

*While this is a real telling of history, I am also not one of those bodyworkers who is anti-western medicine. Thank god for how it is has literally saved the lives of many who I love. And oh grief for how the fierce caring and healing work of some of its members has been shaped and harmed by the insurance industry, by the cultures of consumerism and competition, and by the disconnection of a single life from the rest of all life.

** A few people have reflected that the illustration about this article is most often used to get people to go on diets. I had no idea and want to yell about that. No diets were supported or tried or experienced or demanded in the writing of this blog post. Our bodies rebuild themselves just because they do, not to change their shape but to integrate the enormity of life.

Friday, December 15, 2017

What is healing justice and how would it affect this gathering?

Yesterday I got to record a podcast conversation about the healing justice work at the USSF in Atlanta and Detroit with Cara Page and Kate Werning. I got off the phone and then went back to look at some of the documents we put together in 2010. This is something I wrote after we were already at Detroit. We were talking about how much confusion there was about how healing justice could be a lens on deep movement work, on actions and cultural change. So I wrote this and we printed about 500 copies and spread it in rooms around the Social Forum. Re-reading it I thought, yep, as HJ work often gets perceived as happening in separate spaces from where movement is taking place, this flyer is still relevant. If it's useful to you, go ahead and use it. Love credit it as appropriate.

A conversation takes place about

working conditions for agricultural workers or maybe about housing foreclosures

and you are listening to it when you feel something shift inside. This is not

just an intellectual conversation. This is about your life. You feel your heart

race and a mix of emotions are suddenly flooding through your body. Maybe you

are angry. Maybe you want to cry. It is hard to just sit in a chair and talk

about this as an issue. It seems no one else in the room has experienced what

you have. So you shut down, get quiet, and wait for the session to be done so

you can leave.

You are taking part in an action

exercise, practicing using storytelling as a skill for mobilization. In the

midst of a practice session, you can feel your voice get tight. You were

talking about prisons and violence. It becomes hard to speak. You are

embarrassed because usually you can talk about this really easily. You think of

yourself as articulate. You leave the room as soon as you can, worried that

people are going to remember you, that you didn’t have anything to say. You’re

glad there wasn’t anyone from your hometown to witness you fumbling.

Two people with different beliefs, both undocumented, are

arguing about how to organize in immigrant communities and about the roles of

nonprofit organizations in social justice work. Their argument begins to get

heated. People in the room freeze up, not sure what to do. A few people leave.

Others take sides. You’re one of the people in the room. You don’t know what to

do. You feel like you should say something but you aren’t sure what to say.

You’re afraid they’ll turn on you. Or maybe you’re one of the people arguing.

You don’t really want to keep fighting like this but it’s gone so far, it’s

hard to back down. Or maybe you’re in the room and you say something and

suddenly everyone is looking at you. The conversation ends when everyone leaves

but the tension never finishes. Something got stuck and people leave, feeling

uncomfortable.

There is nothing we talk about in movement building work that is only an “issue.” These are things we have experienced. Our bodies, our communities, our memories carry all of the times when we experienced or witnessed violence, systemic disrespect, or marginalization. When we are working together to change systems and beliefs, we are also carrying the fallout from those systems and beliefs inside our selves.

Healing Justice means taking seriously the effect of trauma, oppression and violence in our lives. It means recognizing that when we are uncomfortable or scared or furious, this is important information. We can learn from this information. We can shift what is happening in our bodies. The role of healing justice practitioners is to come into those spaces described above and to help shift what is happening. Often the reason we get stuck or feel like we need to run from the room or start fighting with someone who can and should be an ally is because of what we are holding. This holding affects how deeply we can dream and how far we can vision. Ending oppression means ending how it exists in our communities and in the systems around us – and it means ending how it lives within our bodies.

Deep gratitude to those building on the ground at the USSF in Detroit, 2010.

Tuesday, November 28, 2017

The Medical Industrial Complex with gratitude to Mia Mingus, Patty Berne and Cara Page (plus others)

Very simply, if we are not careful, all of our healing justice work is going to become just another piece of the machine. If we are not careful, the culturally-grounded, beautiful and deeply loving spaces that we are creating, private spaces with handmade artwork on the walls, will become a node on the organized profit machine that is the medical industrial complex.

The illustration above is a map that Mia Mingus, Patty Berne, Cara Page and a number of other disability and healing justice thinkers put together after a multipart conversation. Mia explains it beautifully and offers more explanation as a tool in our work for collective liberation.

When I was in my late 20s, after having dropped out of college for about 10 years, I decided I wanted to finish my degree. I had also been living away from the US and so, upon coming back, decided to enroll at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. I liked that Antioch was focused on experiential learning. As students we were less in the classroom and more in the world, doing internships and learning by just being in life. A more radical and glorious bunch of people you couldn't find. It was there, amidst the corn fields and old wooden farm houses, that I started to wonder if I had been duped. After all, it was perfect. We had a contained bubble of hundreds of incredibly radical folks, mostly young and very very able-bodied. Everyone slept with each other. Fought with each other. Introduced each other to friends living in other contained bubbles in other towns and cities. And we grew perfect and strong. And I remembered how the immune system has evolved to operate: when there is a danger to the body that would take a lot of energy to destroy or expel, it contains it within a membrane, something that mimics being connected to all life but is, instead, off doing its own thing and not negatively impacting the body as a whole. I sat there in Yellow Springs and felt the containment, even as we were all talking about revolution. How very non-threatening we all were.

I think about this when I think about my work at the People's Movement Center in Minneapolis. I am so grateful for our work. I believe it is important. But I also believe that, if we aren't careful, we are going to become that node on the top right of the Medical Industrial Complex map; a contained little membrane where those who have access, like a secret code, can come through our doors and be there, in the closed off membrane along with the rest of us.

I don't actually think that is happening. I think this is happening. I think both are true. I love the vision that Mia offers in the essay that goes along with the chart:

I am inspired by the possibilities that can be grown out of the rich fertile ground where disability justice and healing justice meet and overlap. I ache for more healers that don’t continue to perpetuate ableist notions of how bodies should be (or strive to be) and for disabled folks who don’t have to only know “healing” as a violent word because of our histories of forced healing, cures and fixing. I get excited about practitioners who have accessible spaces and practices that can hold all kinds of bodies and minds; and collective access and care that allows more and more disabled people to be less and less bound to the state.

I assume there are healers and other practitioners reading this blog. If so, I link arms with you and say, here is our struggle. We have a large public, a medical industrial complex, which is how most people, particularly those who are poor and Black and Brown, get their care. This is a system designed to manage people, to weed out the "abnormal" from the "normal," a process of eugenics I wrote about in an earlier blog post. There are also significant powerful people working in this system who are trying to make change, to remain relational, to shift healthcare as control into something that recognizes our complex humanity. I want to be in community with those people and with you to learn how to do all of this: to do the kind of transformative liberated work that is not possible within the bounds of most parts of the medical system and, at the same time, to refuse to let ourselves be privatized. Not a single one of us can heal until all are healed.

Monday, November 20, 2017

Healing within the context of land and history

This is a week when people are either celebrating or resisting the story of how first contact between settlers and Native people happened. This is something I wrote as part of The People's Movement Center, as we sat within the questions asked below. Any mistakes I have made in the telling of these stories, especially the stories that are not my history to tell, are my own mistakes and I am accountable for them.

It always starts with the land….

It always starts with the land….

What does it mean to do healing work, to do any kind of change work when the land below your feet still carries stories that are not finished?

For 50,000 generations people lived right here, on this land that is under my feet. If you, too, are sitting on this land mass that got called North America, then you, too, are living where for 50,000 generations people lived and continue to live. Real people. Complex people. People who were loving and mean, who laughed and who got overly dramatic. People have lived here, right here, before the glaciers came and after, lived here for, as the stories tell us, 50,000 generations, that is how long we were here. Some of the stories of those times are still here, held by the grandmothers and shared with the children. Some of these stories are gone, scooped out along with water from the slough, dried out and then dust flown in the wind. Ghosts that scattered along with top soil, settling in the cracks between here and there.

This the Dakota homeland, here where I live. My home is about 3 miles from the confluence of the Mississippi and MInnesota Rivers, Bdote, the Dakota homelands.

This is land that is soil on top of sand, loose below us where the glaciers ground their way down through mountain and stone to leave sand and boulders, soft land that lets the water run through it, weaving and snaking its way into rivers and springs. This is a land where there is water.

50,000 generations of real people lived here and they did many things but there is one thing they did not do: they did not forget their relationship to the land and all living things in relation to that land. They did not bring the violence of disconnection and control that destroys life. This is why they could live here for 50,000 generations, within a land that was wild even as it was known, was loved even as it was farmed.

This is land that is soil on top of sand, loose below us where the glaciers ground their way down through mountain and stone to leave sand and boulders, soft land that lets the water run through it, weaving and snaking its way into rivers and springs. This is a land where there is water.

50,000 generations of real people lived here and they did many things but there is one thing they did not do: they did not forget their relationship to the land and all living things in relation to that land. They did not bring the violence of disconnection and control that destroys life. This is why they could live here for 50,000 generations, within a land that was wild even as it was known, was loved even as it was farmed.

I work and live in south Minneapolis. Dakota people hunted and their children played right where the pavement runs through. Their families were here in 1500 when French trappers first portaged and then river-wandered from the northern lakes to the southern prairie and oak savannah.

I am not going to do this alone. If you are reading this, I want to know: Do you know your original peoples and your traditional ways? If they are not your people, then do you know the people original to the land where you live? Do you know the people who walked the land for generations before you rented your apartment, bought your house, planted your garden, and put out your recycling bins? Why are you reading this story? How do you want it to help you?

20 generations ago is when the first settlers arrived to the northern parts of this land, bringing with them the separation that they had already learned on the lands where they began. They brought their understandings of private property and land ownership and they began to settle. These people were French trappers who wandered rivers and lakes making business deals with original people. After them came the army, first wave of the surge that would take trees and furs and ore including someday oil from pipelines, the army came and over time drove the Dakota villagers who had lived along the river banks for generations, drove them further away. Some settled along Bde Maka Ska, settling with a small farm where Lakewood Cemetery is today. Here is where Chief Cloudman lived and where some of the first Christian missionaries also set up, working to enforce western language and cultural traditions with the intent to break the cultural link the Dakota people have with the land. When you look at very old maps, there is a trail that goes from Bdote to Bde Maka Ska and it passes very near to where my work, the People’s Movement Center, stands.

By the time the French and then the army came, there would have been squatters here, too; Europeans who came and just put up a tent, a shack, a rough house. So many of those early settlers were young people, just like young white US travelers today, young people who leave their homes to go to different lands where they can have adventures before they go back home to their families. Collecting stories like empty skulls. Some people came because they didn’t fit in back home, because it wasn’t safe anymore to be back home, or because they felt the call deep inside for something that was wilder than cities and farms. Some became friends with people from local tribes and some did not. They hunted. They fished. Sometimes they farmed and then they died or else, when the city got bigger they went further north and settled in whatever corner they could find. I think of them when I drive up to northern Minnesota and see the houses that are made of plywood and twine, the old white men with beards down past their knees who live by hunting and gathering, signs with pictures of guns posted along their fences.

And there were treaties. Did you know that even as the first settlers began to establish St. Anthony and what would later become St. Paul, what is now Minneapolis remained only Dakota territory until 1851? 50,000 generations lived on this land and it is only been seven generations since settlers overtook this Dakota territory. Seven generations since the Twin Cities went from being held by original peoples to being controlled by settlers. Seven generations against 50,000.

Agreements between nations, agreements like we have free trade agreements today, agreements as a tense compromise between the rich and greedy and the poorer in need of work. Or the poor and greedy, hoping to be the winners this time. Land gluttony. It happened fast, like a plague. Within a generation, the balance tipped from mostly original peoples to those who were not. In 1862 the US government passed the Homestead Act, opening up ceded (and violently taken unceded) land for settlement. That same year, 1862, Dakota families were hungry and had not received the food and supplies promised through treaty. Young people, frustrated with weeks of promises and growing hunger, fought, protested, raged, and this became the Dakota War of 1862. President Lincoln sent in troops, many the same troops who had just fought in the Civil War, and at the end of the battles, those Dakota families remaining along the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers were removed, exiled, such violence, the uprooting of a people from their land, their history. Their warriors, 38+2, were murdered and after all of that, what mattered most to those who came was that now there was more land. The stories shared in newspapers to the east told the stories of land, free land, not the stories of the families whose lives had just been traded for federal profit.

More settlers came, buying farms along the Minnesota River, the Mississippi River, the St. Croix, spreading and calling their families to come and then spreading further. Trees cut down to make railroad ties. Swamps filled in. Banks and more banks opening and then closing as money changed white hands, exploded into wealth for some and disappeared over night for others. The squatters were kicked out and now land was bought with legal paper. Irish carpenters and tavern keepers, Swiss and Welsh laborers, German butchers and cigar makers, English masons, and Scots bakers joined farmers from Germany, Canada, and older areas of the United States, wagon makers from New York, hotelkeepers from Virginia, lawyers and merchants from Pennsylvania, millwrights from Ohio, ministers, teachers, and tailors from New England, and French-Canadian voyageurs and blacksmiths to spread over Minnesota including these neighborhood blocks just outside my door.

More settlers came, buying farms along the Minnesota River, the Mississippi River, the St. Croix, spreading and calling their families to come and then spreading further. Trees cut down to make railroad ties. Swamps filled in. Banks and more banks opening and then closing as money changed white hands, exploded into wealth for some and disappeared over night for others. The squatters were kicked out and now land was bought with legal paper. Irish carpenters and tavern keepers, Swiss and Welsh laborers, German butchers and cigar makers, English masons, and Scots bakers joined farmers from Germany, Canada, and older areas of the United States, wagon makers from New York, hotelkeepers from Virginia, lawyers and merchants from Pennsylvania, millwrights from Ohio, ministers, teachers, and tailors from New England, and French-Canadian voyageurs and blacksmiths to spread over Minnesota including these neighborhood blocks just outside my door.

Where were your people between 1750 and 1850? Did they have sovereignty over their own lives? Were they owned or did they own? Do you know the stories of who you were for those years? Do you know specifics or only something general? What happens for you when you think about that time, about what you know or don’t know? How close do you feel to them? Seven generations, .00000001875 percent of the time that we have been evolving on this planet, .013 percent of the time since the last ice age crossed the land below our feet. What do you know about your people from just seven generations ago? Six generations ago? The time of your great-grandparent’s great grandparents.

The city grew. US policy towards the original peoples moved to Kill the Indian/Save the Man, and boarding schools were set up, the children and grandchildren of those who lived along the river, who might have hunted where my home now stands, being removed from their families, from our families, and sent to Christian schools to disappear the Dakota, the Anishinabeg. And the memories of those who remembered when there were more oak trees than people faded in the way that the stories of our great grandparents become only vaguely told sentences without the feeling of what it was like.

But not all of the stories disappeared. And they did not win. Even as the story, the violences, are not finished it is important to pause here and say this: they did not win. The stories are not gone. The people are still here, stronger and fighting back. Which side are you on?

The city grew. Flour mills and lumberyards growing fat off of the homesteading of the prairie and the cutting of the great north woods. And Minneapolis grew. Almost tripling in size between 1900 and 1950, we are creeping into the memories of your grandparents and parents, of the stories those of you who grew up here might now remember.

The city grew. Flour mills and lumberyards growing fat off of the homesteading of the prairie and the cutting of the great north woods. And Minneapolis grew. Almost tripling in size between 1900 and 1950, we are creeping into the memories of your grandparents and parents, of the stories those of you who grew up here might now remember.

In 1910 all over the United States, “racial convenants” were legal instruments inserted into property deeds that prohibited people defined as “not Caucasian” from purchasing or inhabiting homes. This happened all over the country and also in south Minneapolis. The list of excluded groups reflected the racial assumptions of developers, real estate professionals, and homeowners. A common covenant read, “[this property] shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent.” Penalties for anyone who tried to break these covenants was severe and included losing your home and any money you had put into the property (equity). Looking at the map linked above, you can see the demographics of south Minneapolis laid out along with these 100 year old expression of legal segregation. Each economic development choice, when weighed against these racial covenants, defined the city, who lived in it and therefore who had access to all of the benefits of a livable city.

Who in your family was alive in 1914, how many generations before your birth? Did they live in the US? In Minnesota? How many of them lived in Minneapolis? Or were they even allowed to? This was the time of eugenics in the United States, when people of color, the poor, folks with disabilities, queers were being institutionalized, sterilized. Radio was new. Catholics were following Father Coughlin by the millions as he ladled up his version of sacred normalcy. This was World War 1, the Great Migration. When many of your family stories are still remembered. What did your grandparents, great grandparents tell about this time? How did it make who you are today?

This is around the same time when the Mexican community in south Minneapolis began to grow. Sugar beet companies in rural Minnesota began to recruit families to come up from Texas to work in the sugar beet fields. Some of the betabeleros returned to Texas during the winter months but others stayed and built homes in the Cities. While the largest community lived in St. Paul, a smaller community lived near the PMC on Chicago Avenue and further north to Nicollet avenue. In the 1930s and 50s, as the sugar beet industry began to wane and as economic controls after the Great Depression were put into place, many of these families were deported, both those who were undocumented and those who were legal residents. Just like now.

The Great Depression and everything afterwards when frightened people were looking for scapegoats. In poorer neighborhoods in Minneapolis, unemployment was over 25% In 1931, nationally Minneapolis became known for its food riots as neighbors broke into grocery stores, stealing food to feed each other. In 1931 white residents stormed a Black family's home in south Minneapolis, demanding they leave, demanding that their neighborhood stay white. Economic fear and white control have always gone hand in hand.

What stories exist in your family from the Great Depression? Were they here in the US? Food and housing insecurity was at an all time high. People both gathered together in collectives and support systems and they turned on each other, looking for people to blame. Eugenics continued to gain national traction as the reason for everything bad. During this period, 2,350 people were involuntarily sterilized in Minneapolis, most of them defined as “mentally ill” or “mentally deficient.” How did your family fit into this story? What themes from this time are coming up again today? Why?

The Minneapolis General Strike of 1934 ended in riots with the police opening fire on labor union organizers and protesters. Two were killed and 67 injured. The strike closed down all transportation in Minneapolis and the state declared martial law. Many of the workers lived where I live and where I work. This was 7 years before my mother was born. I grew up hearing stories of the Great Depression and of the strikes from my great grandparents and grandparents. This is recent history. This is yesterday.

In 1934, the Federal Housing Administration developed a system for classifying homes for home buyers based on their resale value and were marked green for the most desirable and red for the least desirable. And thus was redlining born. At this time, race in Minneapolis was defined as Native-born white, foreign-born white and Black. In 1930 and 1940, Black families made up .9% of the population. If you pay attention to local politics, then you know how redlining impacted North Minneapolis. Funds dried up. Economic segregation became tied to racial segregation. And that history has still not recovered. Four blocks north of the People’s Movement Center, where I work, just as you cross Park Avenue, you enter the redlined zone. The PMC was not in a redlined area but the PMC is on the transition space, the border. Two blocks down, at 41st and 4th, was Mrs. Little’s boarding house. Here is where Black folks new to town stayed in order to figure out their next steps. What we know about all border towns and border areas is that this is where the likelihood of conflict – as well as of creative transformation and power – increases.

In the same year, the Indian Reorganization Act demanded that, in order to be recognized by the federal government, tribal communities must organize themselves in cookie cutter ways, not by their own traditions and cultures, but by a management system that made sense to the government. And for those who were not tied to a tribal community through a reservation or for those tribal communities that the federal government decided no longer existed, the US brought in a policy of assimilation, moving Native peoples to urban areas for resettlement. And so some of the children and grandchildren of Dakota and Anishinabeg peoples were moved into federal housing in Chicago and Cleveland and Milwaukee… and also to south Minneapolis, back to their original lands but now as relocated persons within their own land.

Did you grow up in an urban area? What do you know about your neighborhood in relation to redlining or the Indian Reorganization Act? Did you grow up in a rural area? What was the racial make-up of your community? Where did who live? Was there formal or informal segregation? Were there visible indigenous people, indigenous to this land? Again, what did this all mean for your family? What did you not know because of these things? How do these stories relate to your family's origin stories, the story of how they came to be? Of where they come from and who they are? Is there a connection or were those stories told as separate things?

There is so much more history to tell about this land where I now live. There is history to tell about the land where I was born, Cleveland, Ohio, the land of Tecumseh and the first pan-tribal resistance to the violence of settlement. There is history of busing and civil rights, history of hate crimes like the Duluth lynchings in Minnesota and the Black uprisings in the Hough neighborhood in Cleveland the year I was born and multiple times after. There are also so many stories of survival and resilience in all of these lands where I live and where I come from.

As healers and healing practitioners, these are the stories, the contexts that weave through the bodies that come to see us, sometimes visible, often invisible. This is the broader imprint that defines how the person sitting across from us feels: the food they eat, the air they breathe, the violence their people experienced or enacted, the shape of their home growing up and their home now, whether or not their was a yard, a safe place to play, other children who looked like them, the concern of threat from the sound of a doorbell or the fact that their neighbors would call the police if strangers came by. Private property or public housing, there are stories behind those homes that come up through the floorboards and settle in our bones.

As healers and healing practitioners, these are the stories, the contexts that weave through the bodies that come to see us, sometimes visible, often invisible. This is the broader imprint that defines how the person sitting across from us feels: the food they eat, the air they breathe, the violence their people experienced or enacted, the shape of their home growing up and their home now, whether or not their was a yard, a safe place to play, other children who looked like them, the concern of threat from the sound of a doorbell or the fact that their neighbors would call the police if strangers came by. Private property or public housing, there are stories behind those homes that come up through the floorboards and settle in our bones.

Plantain root. Dandelions. Some of the elms planted along the boulevards, pineapple weed, thistle, comfrey, all of the kinds of clover, motherwort, mugwort, and mullein. These are all medicinal plants. They grow in the alleyways behind Minneapolis homes, you find them along the roads and in public parks. Their ancestors were carried over in the pockets of settlers who brought their pharmacy with them, seeds they spread in their gardens who then escaped and became, like their sowers, transplants that crowded out what had been here before. They are medicinal plants. They heal. They are also colonizer plants. They have crowded out plants that are Native to this land, the plants that form the oak savannah and the water logged sloughs of what is now south Minneapolis. Both of these things are true.

And this is the challenge in being healers on this land who are not original to this land. This is the generosity shown by those who are original to this land who turn to those who are not in order to heal.

And this is the challenge in being healers on this land who are not original to this land. This is the generosity shown by those who are original to this land who turn to those who are not in order to heal.

There are ghosts that walk our streets, right this second, as you take a deep breath and listen to the stories that you know and don’t remember, do you know who you are and why you are here? Do you know what your life has been created for? And why you are here, on this page, hearing this story, and remembering? What is that you are here to heal? And what is it within you that needs to be healed?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)